We know motivation when we see it in others. The colleague that always seems to have gone the extra mile (or two!) and not just completed her project, but also pilots a new technique in the process. The co-worker who manages to finish the report by deadline, but you noticed he also found time to take his kids skiing on Friday afternoon. The manager who not only takes the time to understand departmental struggles, but puts in the extra time organizing a workshop to get the team thinking about how to overcome challenges in new ways.

Are these people superheroes who happen to walk among us mortals and make us look all the more fallible? It turns out, probably not – they have simply employed some powerful motivation techniques that we all can use to cultivate our intrinsic sense of purpose.

So how do we harness motivation to our advantage? In a previous article, Goal Setting Techniques That Actually Work, we talked about some approaches for minimizing the motivation necessary (making the most of what we already have). This is done by breaking big goals down to smaller tasks and creating systems to make tasks automatic. And in Organizing Techniques That Actually Work, we looked at some methods for making the best use of our time, energy, and attention.

A third approach, and the topic of this article, is how to maximize the motivation available, and cultivate the sources of your motivation.

Let him who would move the world first move himself. –Plato

How does motivation work?

Before we look at ways to cultivate motivation, it helps to understand what motivation is, and how it works. The traditional view is that motivation is the precursor to action. Build up enough motivation and you’ll move onto action. But where does that motivation come from? Presumably, it comes from a good idea. You get an idea, you probably get a lot of ideas. Some of them lead to motivation and if you get enough of that motivation it turns into an action. There are two ways of looking at this process, the stair step and the cycle models.

Stair step model of motivation

In the stair step model, you have to get that first step of an idea. If the idea is big enough, it leads up to the motivation step, and enough motivation leads to the action step.

Say it’s Saturday afternoon and I’m sitting on my very comfy couch, watching Netflix. I get the idea to lace up my sneakers and go for a run. I ponder the idea, but it hasn’t turned into motivation yet so I remain reclined, waiting for Netflix to ask if I’m still watching. Then I have another idea, what if I promise myself a fresh smoothie after I run? Now that is a better idea, and maybe good enough to spawn some motivation. To add to that, if I’m going to bother to go running, I might as well check in on my Strava app and see if I can beat my co-worker’s new PR for the week. Viola, now I’m out on a run!

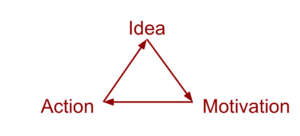

Cycle model of motivation

Another way to look at motivation is as a cycle, with no one starting point. We could start with an idea, or we could start with an action, and build on it. We could even start with motivation, and let the idea come from that.

How does the cycle model work? You can start with a motivation that leads to action. Taking the same scenario where my goal is to go for a run on Saturday, maybe I could start the day (when I naturally have more motivation) by laying out my running clothes and making a date (known as a pre-commitment) with my wife to run at 2pm. Maybe after that run I get the idea to start a running group on Saturdays at 2pm every week. Whether my wife is into it or not, I’ll always have someone counting on me to run. So the motivation led to action, which led to an idea, and that idea led to its own motivation. The cycle can start building on itself.

You can also start with the action. A writing technique I learned from the 2000 film, Finding Forrester, with Sir Sean Connery, is the practice of sitting down to write even if you don’t know what to write. The technique goes like this, you start writing before you have the idea or the motivation, just write whatever comes to mind. When the writing starts forming into something (the idea), go with it.

I’ve used the same technique, slightly modified, when tackling an intractable software programming problem or bug. Maybe I’m not able to get my head around how to solve the problem, but I do know some steps I’ll eventually have to take, even if they are trivial, such as logging time, connecting with a database, and some kind of UI. I can start with these actions, and sometimes make some headway of any kind breaks the floodgates. Once I step into action, I’m able to get more motivation to proceed with the piece that was stumping me.

Motivation can become self generating, or intrinsic, if you know the tricks. When motivation is generated internally, there’s less need for external or extrinsic motivators.

Opportunity is missed by most people because it is dressed in overalls and looks like work. –Anonymous

Extrinsic versus intrinsic motivation

Most businesses are fundamentally built on the concept of extrinsic or incentive-based motivation. The idea is that if you give people something, they will behave in a way that is beneficial to what you are doing. If you pay your employees, they support the business. If you don’t pay them, they won’t.

There are some problems with incentive-based motivation. What they found in Dan Pink’s book, Drive: The Surprising Truth About What Motivates Us, is that incentive-based motivation can be great for algorithmic tasks where you get a certain bonus for a certain amount of work, but it doesn’t scale well. If the bonus is $10 this week, next week $8 isn’t going to do it because $10 has become the baseline of expectation. Now it will need to be $12 to provide added incentive.

Another problem science has found with incentive-based extrinsic motivations, is that they have an inverse effect on non algorithmic, or heuristic tasks. Offering people bonuses for creative work actually causes less delivery of work and less creativity in the work.

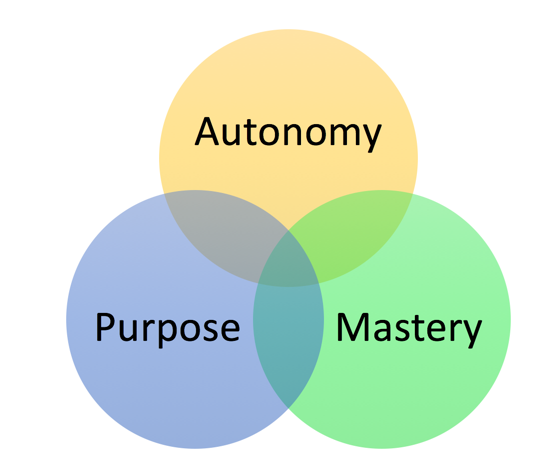

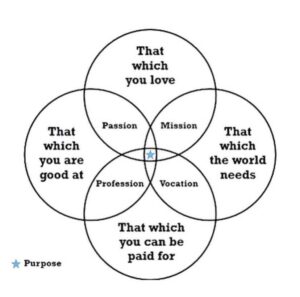

Intrinsic motivation, on the other hand, is derived from within. Rather than external drivers like money, praise from others, or rewards and penalties, the three primary drivers of intrinsic motivation have been identified as autonomy, mastery, and purpose.

Intrinsic motivation, on the other hand, is derived from within. Rather than external drivers like money, praise from others, or rewards and penalties, the three primary drivers of intrinsic motivation have been identified as autonomy, mastery, and purpose.

Autonomy is the desire to direct our own lives and can be further broken down into four areas, the 4 T’s, Task (what you do), Technique (how you do it), Time (when you do it), and Team (who you do it with). Mastery is the goal to continually improve at something that matters. And purpose is the desire to do things in service of something larger than ourselves.

How can we harness the power of purpose?

Of the three intrinsic motives above, purpose is usually the strongest, and the focus of this article. Often we consider having a purpose as something that is fixed. Either we work at a non-profit for a meager paycheck saving the world, or we have a normal job that pays more for doing something we don’t always care about. However, no matter what your job is, it can have some underlying purpose. You don’t just deliver packages, you facilitate reliable global commerce. You don’t just manage people, you create an environment where people can bring their best qualities to mutually benefit themselves and the organization.

While your purpose may not be a total match with that of your organization, identifying where the compatibilities are is one way to garner your motivation. Simon Sinek, author of Start With Why, How Great Leaders Inspire Everyone to Take Action, has defined an organization’s or individual’s purpose, cause, or belief as their Why.

While your purpose may not be a total match with that of your organization, identifying where the compatibilities are is one way to garner your motivation. Simon Sinek, author of Start With Why, How Great Leaders Inspire Everyone to Take Action, has defined an organization’s or individual’s purpose, cause, or belief as their Why.

In an ideal world, you have a high level of overlap between individual and organizational purpose and the connections are easy to make. In other cases, it may be as indirect as your job provides a paycheck that affords you living expenses and enough free time to participate in the activities that match your Why. Understanding and recognizing the connection between your Why and your company’s Why, to whatever extent it might be, can increase your feeling of purpose, job satisfaction, and perhaps even life satisfaction.

Working in the public sector, there is no lack of purpose in the work that we do. But for me, the aspect of our work that resonates most with my personal Why is working with teams to move from a collection of individuals to a cohesive team that utilizes the best characteristics of every member. As a developer, this is not always something I’m tasked with, but it’s unique to the work I’m able to do, and enough to carry me through the days that feel less relevant. On the days where my primary focus is working with and helping my teams, and even more the days where my teams succeed beyond expectations, the work feels effortless and at the same time worthy of the intense effort I put into it. Knowing those days will come makes it easier to find the motivation to get through the harder days in between.

How do we inspire motivation in others?

Once you understand how motivation works, and how to cultivate it, it’s easier to find an intrinsic purpose for yourself. Now, how do you inspire your team, your employees, or your kids? How do you avoid the traps of extrinsic motivation and give others the intrinsic motivation you want them to have?

The short answer is, sadly, you really can’t. What motivates us is as unique to each of us as our fingerprint or DNA. We can’t use our own motivation for others just as we can’t slip on someone else’s shoe and expect the right fit. The motivation I use for getting off the couch on Saturday afternoon to go for that run isn’t going to be identical to what works for you.

However, an organization can take the following steps toward encouraging intrinsic over extrinsic motivation. Here are some of the things I strive to encourage on my teams:

- Embody and demonstrate the principles of motivation

- Teach intrinsic motivation approaches and techniques and avoid extrinsic motivation approaches when possible

- Create a safe environment for motivation (including the ability to try and sometimes fail)

- Identify and promote the organization’s Why to help attract clients and employees with the same (or at least compatible) Whys

- Coach others to help them identify their personal Why and how it fits the organization’s Why

What’s important is knowing that we each have the capability to find our unique motivation, whether the goal is a Saturday run, or something completely different. We can all work to make an environment where people are free to explore their own drivers of motivation and find what really fits best. With a little extra effort, we can also guide others in their search, knowing that finding their drivers will benefit both the individual and the organization.

Learn more

- Send us your favorite motivation tricks

- Contact us to talk about how we can help motivate you to start your next custom application project

- Goal Setting Techniques That Actually Work: How to create high quality goals to transform you and your organization, by Kevin Ferguson

- Organizing Techniques That Actually Work: How a few good organizing techniques can help you get your most important things done, by Kevin Ferguson

- Kaizen Techniques That Really Work – White Paper: Planning strategies that can transform you and your organization through continuous improvement, by Kevin Ferguson

Videos

- Drive: The surprising truth about what motivates us, RSA ANIMATE video, by Dan Pink

- Why Good Leaders Make You Feel Safe, TED Talk, by Simon Sinek

- Grit: the power of passion and perseverance, TED Talk, by Angela Lee Duckworth

Podcasts

- The Myths Of Motivation, Accidental Creative podcast, by Todd Henry

Articles

- How to Motivate Employees to Go Beyond Their Jobs, Harvard Business Review, by Mark C. Bolino and Anthony C. Klotz

Books

- Start With Why: How Great Leaders Inspire Everyone to Take Action, book, by Simon Sinek

- The Motivation Myth: How High Achievers Really Set Themselves Up to Win, book, by Jeff Haden

- Find Your Why: A Practical Guide for Discovering Purpose for You and Your Team, book, by Simon Sinek, David Mead, and Peter Docker

- Drive: The Surprising Truth About What Motivates Us, book, by Dan Pink